A philistine approach to art

Bring on the Philistines

I’ve always been literary, but have rarely visited art museums. When I got the opportunity I had to start my art education from scratch.

Like most citizens of the middle class I absorbed the idea that art expresses the best of the human spirit, and demands an appropriate reverence, but in my opinion such reverence is a mistake.

When I visited MOMA in New York, and the Louvre in Paris, I gave myself full license to be completely judgmental. This means setting aside any fear of coming across as a bourgeouis philistine, and making many judgments without any formal education in art criticism or background in art history. It means making judgments which one is not entitled to make, in a sense.

I do not claim that sweeping generalizations will help you become an educated and informed critic, someone making sound and well-established judgments.

But I do claim this arrogant approach has helped me interact emotionally with the art I have consumed. In so doing I have discovered my own taste, and the embarrassment of unpopular opinions (which I will share shortly) is outweighed by the pleasant surprise of a discriminating taste.

We can’t make judgments without some standard or other, and the more I make these judgments the more I discover and grow my own philosophy of art.

Surrealists Yes, Impressionists No

In MOMA I enjoyed many of the surrealist paintings, finding the concepts entertaining. They have many of Picasso’s work. While he is not my favorite, his power is unmistakable.

I dislike most Impressionist works - they are thoughtless compositions of landscape made a bit blurry. Another way to say this is that most Impressionists are not Monet, and most Monets are not his waterworks.

I dislike most Pointillist works on the same grounds. The technique of using many small dots to paint does not in itself add much to the scene. My computer screen uses small dots, and can make pictures blurry.

Further, I dislike works that simply depict some 18th-century functionary or merchant without adding much to the portrayal - it is simply a photograph done in oil. There are many paintings in this category in most museums. They are of historical rather than aesthetic interest.

Most portraitists (and photographers) do not have the ability of Lucian Freud and Rembrandt to capture a lifetime of character and personality.

The Louvre does contain several wonderful works by Rembrandt - I look forward to many years of visiting his Saint Matthew and the Angel.

It is the best work of his they have. Rembrandt captured so much of the person he imagined, the guiding angel looks strong rather than ethereal.

Speaking of ethereal, Botticelli cuts such a contrast with the surrounding artwork.

Light, golden, ethereal, hazy, I wonder if Italy has more of his contemporaries and if any are closer in technique.

A painting can capture textures and colors hard to get otherwise - many cathedrals resist an easy photograph. The golden light gently washing over the walls, the color of the brilliant stained glass (hard to replicate these days) are completely lost in my photographs. The place looks stoney and cold, I carry the actual experience away in my memory as best I can.

Similarly for dark and moody scenes, which lend themselves so well to a chiaroscuro technique. The Louvre’s 18th-century French collection has many wonderful works in this vein, dark cathedrals, cavernous underground scenes. Cleanly executed, many of them, a bit rationalistic, but not blueprint-ish.

For example Rosa’s Shade of Samuel, such rich darkness.

One room here contains exclusively dark and moody paintings. These are worth seeing because the paintings themselves, and also what they depict, are very hard to photograph well.

The 17th-18th century Italian collection contains many uninspired works, some of which are simply incorrectly executed - they are blurry or have poor perspective, not in interesting or intended ways. Bits of tat that depict religious scenes but do not add any thought to the subject matter.

The architecture of the Louvre in many places is far better than the paintings it is meant to house. Be sure to look up as you walk through! Also you could spend much of the day outside on the grass, or just sitting with the buildings. There are wonderful statues on several stories of the outside of the Louvre. By the way, the entrance to the museum is through the large glass pyramid.

Abstraction

An abstraction must be an abstraction of something in my opinion, although I certainly admit that higher levels of abstraction may require some training to appreciate.

Still, if you have seen one Pollock you have seen them all. Concept art is risky: your concept might be simple and easily grasped. Paint randomly thrown, all right, that’s as deep as the pattern goes, although the bright colors are nice.

This electric painting stood out from everything around it, I was pleased to discover it is an El Greco.

I did not expect to enjoy much of the African collection, but in fact many of the pieces there displayed an astounding and thrilling level of abstraction.

And her counterpart:

The blue man needs to be walked around to appreciate how his face stands out in an ncanny way.

I have no misguided sense of political correctness here - many of the pieces in this section are interesting anthropologically but not artistically.

Note that a painting does not need to act as literature, I think, though that is a valid and valuable aim - those enjoyable 18th-centry French landscapes I mentioned above don’t aspire to commentary.

And of course then there are the compositions which cannot be done in photographs without huge budgets, such as the wreckage of the Medusa.

I have seen photos of this portrait of Charles I all my life, but actually it is one of those paintings adequately represented in photos.

You do not gain much by seeing it in person, unlike say El Greco or Picasso or some of the gargantuan works that cover entire walls. The Winged Victory is stunning and given pride of place.

One other note about the Louvre - like the British Museum, it has jawdropping statues nicked from Egypt and elsewhere, 1500 years BC and more, in mint condition, and just shoved out where anyone can touch them.

I have more than my fair share of anti-authoritarianism but touching statuary and relics, which many people do, is a social norm which should be more strongly enforced. Human touch degrades these, and they belong to the ages.

This bleak landscape is by one of the few Scandinavians they have got.

Tyler Cowen’s advice to stick mainly with Michelangelo’s work, and Flemish paintings, is very sound, at least if we count the Dutch painters (like Rembrandt) among them. Although as I said there are 4 or 5 works in the African collection well worth seeing.

The collection of Marie Antoinette’s and others’ objets d’art can also be skipped - this is just lavish furniture and kit. We can manufacture these things today, what bastards they were to steal all this.

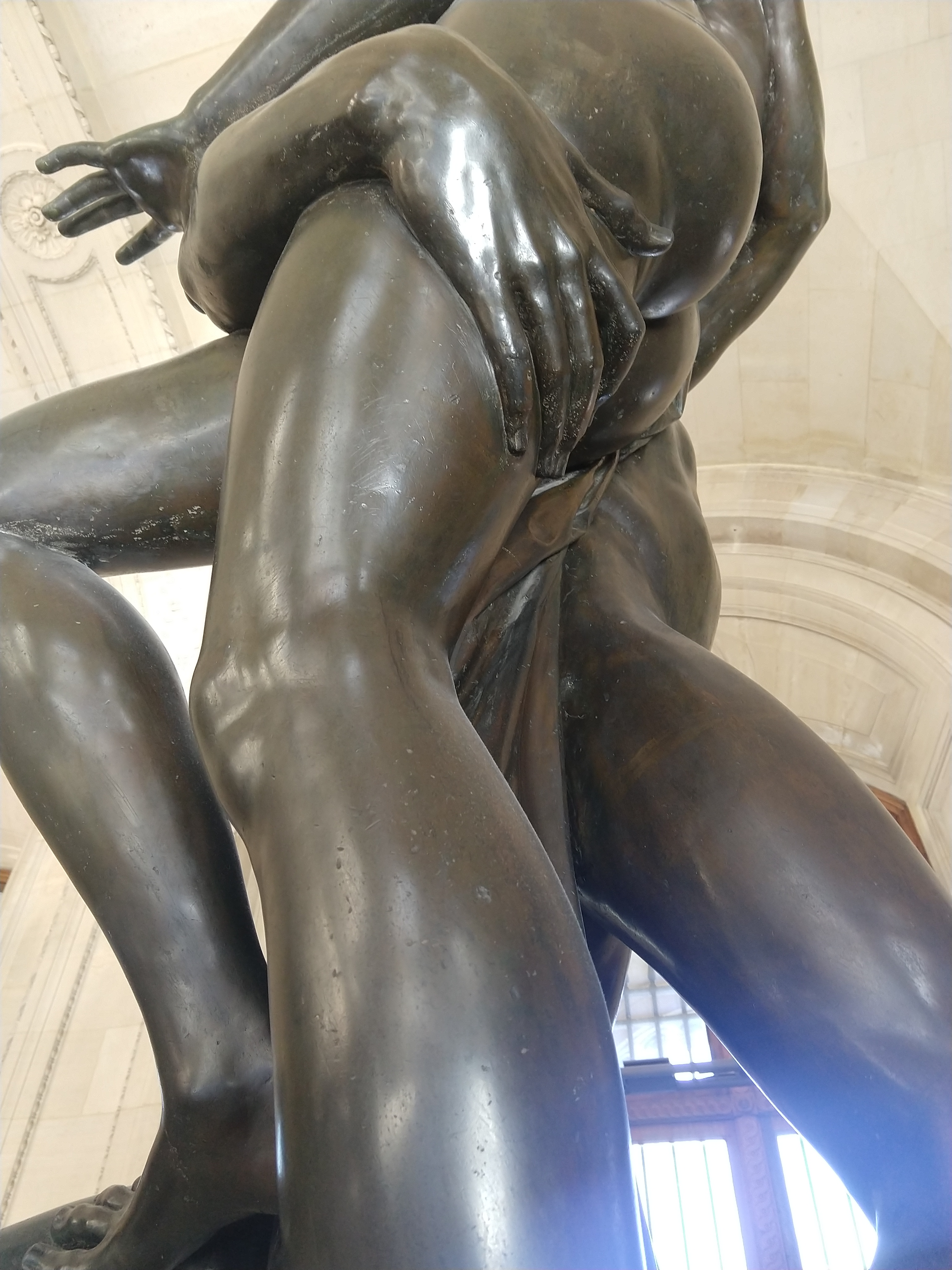

After you have appreciated the callipygous form on display here, notice how the hands indent the skin they are gripping - but compare with Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina.

Bernini is vastly superior.

The colors here are even more vivid in person. How he must have worked at the chemistry of his paint!

Campi’s work is amazing, but a bit bonkers. Is that the Death Star impinging on the Crucifixion?

Toward a Philosophy of Art

After all this it seems I’ve articulated a philosophy of art criticism. In general I want my art to add something to the conversation.

It can capture a visual experience you can’t get otherwise, in light and color or in events. Or it can comment as a work of literature. It can be a bit conceptual, like the surrealists or some abstract art, giving us new vocabulary to see, giving us that wonderful dopamine hit of understanding, of abstraction, of compression.

But in general I will not respect something just because it’s made of oil and canvas. Lazy depictions of historical personages, religious or mythic scenes, landscapes, may have gotten the artist a commission and may make it into the museum but don’t deserve our attention. These are interesting historically or anthropologically but not artistically.