Relativizing the Singularity

The Ordinary Course of Revolution

When Newton published the Principia, he was apotheosized.

To quote Pope’s eulogy:

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:

God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light.

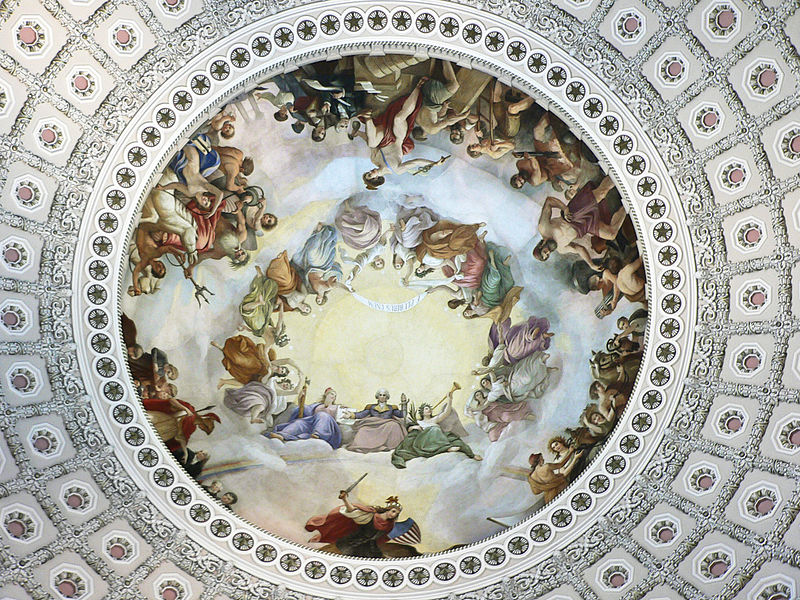

On the ceiling of the rotunda of the United States Capitol, there is a large painting called The Apotheosis of George Washington, showing the great man seated in the clouds, clad in a Roman toga, having become a sort of demiurge.

That painting is absurd, and that sort of thing is what happened to Newton. Around Europe he was hailed in prose and poesy as the god-like intellect, which o’er the cosmos casts its eye of light, that sort of thing.

The intellectual shock Newton dealt by placing physics on a mathematical basis, with a consistent cause operating across the solar system and here on earth, blew his contemporaries’ minds.

A similar kind of shock and awe overtook the Western world during the Industrial Revolution. Mendeleev’s table had come out in 1869, Lovelace and Babbage and Boole were at work, Maxwell and Heaviside and Gibbs back in America were working out statistical mechanics and vector calculus. Lord Kelvin thought there were no more physical laws to discover. You get the sense that the scientists in the late Victorian Age were just overcome with how much they knew, how much they’d discovered in such a short time.

Then, of course, Einstein, Bohr, Gödel, Turing, von Neumann struck, similarly

shattering the accepted worldview. And just as happened to Newton, Einstein in

particular became a massive celebrity, the one who had unlocked the secrets of

the universe.

Then, of course, Einstein, Bohr, Gödel, Turing, von Neumann struck, similarly

shattering the accepted worldview. And just as happened to Newton, Einstein in

particular became a massive celebrity, the one who had unlocked the secrets of

the universe.

By that time, though, Kuhn and Popper and others had enough historical data to begin to think about the process of scientific revolutions. These worldview-shattering, humanity-altering scientific discoveries were to be somewhat… expected.

Instead of greeting every paradigm shift with awe, the scientific community in general became more adept at thinking about uncertainty in their theories. The vocabulary of models took over, a key change, because we can think about a model being more accurate than the previous model, while at the same time permitting uncertainty and the possibility that the model, and the larger scientific model or paradigm within which it is situated, may need to be fundamentally revised.

We have relativized these revolutions. We have placed them within a loosely Hegelian framework of continuing intellectual progress. Our meta-model, if you will, of the scientific process which constructs all our scientific models, now embraces revolution as the ordinary course of scientific work.

I think few of us look back wistfully to the days of Newton or Kelvin, those first heady days of humanity’s discovery of somewhat-accurate principles of the cosmos, and wish we still felt that certainty that we now knew all there was to know. We’re happy to watch the ongoing process of scientific discovery and we hope every year for a new paradigmatic revolution, a tectonic plate theory that will upend all we know.

Today, we honor Crick and Watson, but we do not apotheosize them. No clouds and togas for them! Our awe at the shocks to our intellectual girdings has diminished.

This is to the good, because we can think more sensibly about how to find the next revolutionary idea, and about what comes after the world-shattering idea.

The Technological Singularity

Almost as soon as humanity realized that thought itself could be constructed from smaller, deterministically-programmed parts, we deduced that thinking machines might one day think and feel all that we do, but bigger and faster. The Industrial Revolution would move into mental work, just as powerfully as machines took over physical labor but perhaps more precisely.

The implications of that deduction lay dormant in popular discourse for awhile. Since deep learning became a viable technique about 2006, thanks to Moore’s Law and huge amounts of data on which to train our algorithms, Silicon Valley has renewed its debate over the future possibilities of AI.

Roughly put, the debate is divided between (a) those who believe we can design a superhuman general intelligence that is friendly to humans, (b) those who point out the weak have never been able to control the strong, and (c) those who believe we will unite with our machines to become silicon-carbon cyborgs.

As a result of these advances, we are currently discussing our latest world-altering intellectual revolution. Unlike previous revolutions, the idea of a technological singularity is more technological than scientific, but there’s a similar sense that “this could change everything,” a similarly apocalyptic tone.

The debate is eschatological or apocalyptic not only in the fear that we might not survive it, but also in the sense that a technological singularity would mean the end of intellectual history, in a sense. If it comes, it comes, and then everything we’ve done will be dwarfed. What more is there to say?

A Word with Our Descendants

Now, I don’t know which of those three scenarios is most likely. If we are all wiped out, though, there’s not much to say to the machines or organisms which succeed us and spread through the cosmos.

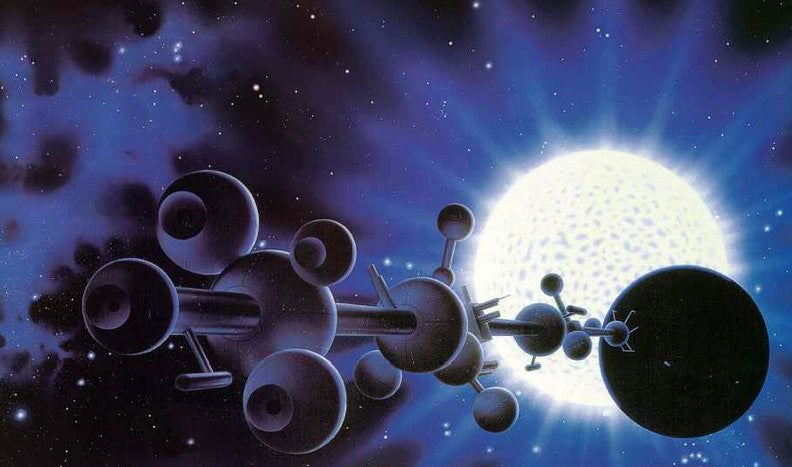

For the sake of argument, let us imagine, then, that our successors are something we recognize. Perhaps they are more-or-less normal humans, longer-lived and served by quasi-intelligent machines. Perhaps they are cyborgs, traces of humans who have evolved and merged into something beyond our comprehension still remaining. Perhaps humans and machines live together as equals, like in Iain Banks’ Culture series.

Whatever they are, even if they do not look much like us, let’s imagine they are something in whose history we played a role. They could look back to us as we look back to the scientists and engineers who created our lavish way of life.

What would our descendants say about the Singularity? For them, it was a revolution in life, a historic step forward. Still, time and again they have encountered similar events of seemingly cosmic significance.

Remember - they say - the first time we figured out how to access a higher dimension? Remember when we hit 80% of lightspeed for the first time? Remember when we confirmed the existence of other universes? Remember when we encountered an older and more powerful civilization for the first time? (Boy were we lucky it was just the Chi Deltans!) Remember when we figured out how to share parts of brains and consciousness?

Keep Your Trousers On

Human history may stop with the Singularity, but if it does not then technological singularities will also become relativized. Our descendants, or the successors to homo sapiens sapiens, will place existential progress into the context of a historical process.

As Silicon Valley debates how and whether to approach the goal of a fully general artificial intelligence, there is no reason to fall into the trap of ceasing to think about what comes after the Singularity. The name itself, of course, implies that there is nothing of importance after the Singularity (where do you go after you enter a black hole? Certainly not home for tea!).

Just as relativizing scientific revolutions can help us approach them and think about their implications and aftermath more intelligently, relativizing the technological singularity could help us approach the matter in a sensible manner.

Putting an existential occurrence into context can help us think a little better about how to approach the design of AGI. And while I’m certainly not suggesting we can forecast with any certainty what comes after the Singularity, I do think we should keep in mind that there may be an after, and we should start thinking about it in sensible ways as soon as we can, as soon as it makes sense to.